What does it mean to be treated as a ghost among the living—which technology reminds us is somehow synonymous with the hearing? Sound Theatre Company sought to answer this question with its opening debut of Aimee Chou’s original play, Autocorrect Thinks I’m Dead, at 12th Avenue Arts this weekend. Chou’s play, directed by Howie Seago, did this and so much more by inviting audiences into the world of deaf culture through a witty and heartfelt subversion of the classic ghost story that painfully recognizes its own marginalized invisibility across the world and the stage.

On its surface, Autocorrect Thinks I’m Dead follows the story of three deaf roommates— Brittany, Calvin, and Merlin—living in Salem, Massachusetts who suddenly find themselves being haunted by what they believe to be the ghost of Alexander Graham Bell. Many in the audience might recognize this man as the inventor of the telephone, but most, likely hearing individuals, will fail to remember his eugenicist background and violent history against deaf people, likely because they were never taught at all.

This is the position in which I found myself upon learning this information for the first time. My utter lack of knowledge about Alexander Graham Bell, audism, teletypewriters, elocution, and even autocorrect was a glaring reminder of the erasure of deaf people within a hearing society. As the roommates begin to uncover the mystery surrounding their haunted house, they equally lay bare the reality of their deaf lives.

Ironically, autocorrect would take issue with this last statement, paradoxically proclaiming a deaf life a dead one. This is ultimately where the play gets its name, poking fun at an issue almost exclusively deaf people face everyday. While a seemingly simple observation on the surface, Chou’s writing goes deeper to explore the implications of being pronounced dead on a daily basis. This makes the play especially well suited for horror, a genre commonly used to make commentary on overlooked aspects of society. Autocorrect certainly does this by recontextualizing what it means to be haunted for deaf characters.

In doing so, it also opens itself up to the wonderful world of comedic misinterpretations. For instance, the roommates don’t immediately realize that they’re being haunted because that haunt initially starts as most often do: slamming doors, loud footsteps, ominous creaking, and general eerie sound effects, all of which are lost on Brittany, Calvin, and Merlin. This incongruence is at once terrifying and hilarious, building to a dramatic irony that both utilizes and interrogates the familiar tropes of its genre in order to illustrate the incongruencies that deaf people face among the hearing. It is evident that Autocorrect is deeply cathartic, in this way. Rather than present deafness as the mere horror show many hearing individuals might ignorantly believe it to be, Chou uses the generic connections between horror and comedy to more aptly emphasize the latter, willfully reflecting the rich inner lives of deaf people and culture.

This is what makes the writing both witty and immature, heartfelt and facetious. Seago’s direction clearly works to make these dichotomies shine, bringing Chou’s writing to life. This is evident in the careful attention paid to every detail in the play. For instance, the set design is beautifully crafted, capturing the essence of an old and weathered New England house from its lofty layout to its interior decorating. Moreover, the screen for captioning feels like a built-in feature of the house and thus seems very natural when it is treated as such. Even the specific green font chosen to project the messages from the teletypewriter onto the stage add to the overall atmosphere of the production. This is equally a prop to the lighting designer, Annie Wiegand, who plays with color and movement in a thoughtful and engaging way that understands its profound relevance in a predominantly deaf story. The lighting’s relationship to the excellent sound design furthermore reverberates this significance to hearing audiences.

Together, all of these elements serve to help the actors bring their characters and story to life. The opening scene establishes a familiar chemistry between the three roommates that immediately introduces the audience to the characters and their culture. Merlin, played by Phelan Conheady, and Calvin, played by Kai Winchester, have a hilarious repertoire and banter that is easily recognizable. Conheady’s eccentric delivery of one-liners alongside Winchester’s dry humor complements each other and the role of their respective characters.

Brittany, played by Brittany Rupik, fits into this group as an equally beloved and funny friend but with a secret edge. Rupik captures this energy effortlessly through Brittany’s posture, mannerisms, and facial expressions, revealing her inner turmoil only through subtle cracks in her carefully-constructed demeanor. As this turmoil is eventually revealed to be the result of secret domestic abuse, Rupik’s performance shines a light on how uneven power dynamics can disrupt safe spaces even within marginalized communities.

This manifests as just another invisible, or intentionally ignored, feature of society that draws interesting intersectional parallels. Autocorrect is full of these types of parallels: possessive ex and demonic possession, spiritual medium and ASL interpreter, poltergeists and religious missionaries, and so on. This last comparison is played for laughs throughout the entirety of the play. The persistence of the missionaries, played by Talasi Haynes and Van Lang Pham, is one that especially resonated with deaf audience members who were laughing and nodding along through these jokes. Haynes’s performance of the ignorant singing missionary won every scene that she was in. As a child of deaf adults (CODA), Haynes clearly understood the comedic nature of her misinterpretations and delivered them perfectly.

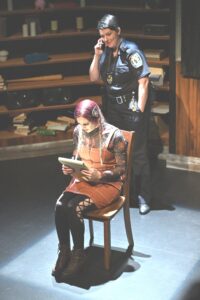

The same is true of Jessica Kiely’s performance as the detective and medium. Kiely encapsulates the frustrated detective trying her best to work around a language barrier, as well as, the spiritual medium who can break through the veil without issue but is incapable of communicating with deaf people. Kiely is both heinous and hilarious as the latter role, blissfully ignorant and willfully unaware of her impact—as hearing people often are.

“In contrast, Pham fulfilled a more pious and subdued role, at first, but ultimately cemented the connection between poltergeist and missionary when he embraced his alter ego, Dr. Bale.” His recitation of audist scripture was a terrifying revelation that equally uncovered deaf intergenerational and religious trauma. In that way, this is the ghost haunting the play, an invisible and tragic history that continues to touch its descendants.

Yet, perhaps the more intriguing observation Autocorrect makes is that of a distinct type of violence: interpretation. On the one hand, as a bilingual production, the play makes clear the significant role that interpretation plays in bridging the gap between deaf and hearing individuals. For instance, Haynes’s character of the interpreter is treated as incredibly helpful by the roommates. Her performance even sheds light on the burden many CODA might face in constantly having to mediate worlds.

However, there is another interpreter who remains unmasked throughout the entirety of the play: Brittany’s abusive ex-boyfriend, Tad, who orchestrated the attacks against them. At one point, Brittany laments that Tad is able to twist her words when translating for hearing individuals, which is why she feels so unsafe speaking out against him. In this way, Autocorrect demonstrates how interpretation can be its own kind of erasure, especially when the interpreter’s role is imagined as passive and is thus made invisible. Of course, this dynamic also reflects that of an abusive relationship—in this case, the tenuous relationship between a deaf person and their interpreter.

As this point is eventually made clear, the minimal weaknesses of this production are ultimately revealed as strengths to its message. For instance, not every ASL joke is translated for non-ASL speakers. There were multiple instances in which I was aware that I had missed something, a misinterpreted sign or gesture lost without context.

Yet, this didn’t detract from my viewing at all. It was a reminder of the play’s limitations and my own about who should be granted access and why. One of my favorite gags in Autocorrect was the characters’s meta-commentary on the captioning screen, relied upon for difficult or lengthy explanations but still incapable of recognizing the word ‘deaf.’ In this way, the play playfully acknowledges the failure of captions to remind the audience that they themselves are not infallible—the captions and the audience. As a hearing person, the conspicuous timing mismatch on the captions were a mild barrier that challenged my expectations of what a play should look like. However, this is nothing new for deaf audiences and I believe it was good to be reminded of that.

Therefore, I would recommend that everyone go see this play. There is something for both deaf and hearing people to appreciate and enjoy.

Autocorrect Thinks I’m Dead. Sound Theatre Company. 12th Ave Arts. 1620-12th Ave, Seattle 98122, Capitol Hill/Pike-Pike Neighborhood. Thur-Sat 7:30, Sun 2pm. Also Mon. Sept. 18 7:30pm

Tickets: https://soundtheatrecompany.org/2023-season/autocorrect-thinks-im-dead/

Check Website for Mask Requirements: https://soundtheatrecompany.org/