Sexual Politics of the ancien régime in France.

The Marriage of Figaro, one of the most popular operas ever written opened to an almost full house Saturday night at McCaw Hall. Adapted from French playwright Pierre Beaumarchais’ equally popular but highly controversial 1778 play of the same name by Librettist Lorenza Da Ponte with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, its reputation is well deserved.

It has everything to make it not just a great opera, but also a great piece of theater: zippy, funny, witty dialogue, a plot where the underdogs win, and most important social commentary about the “sexual politics” of the rich and powerful, which is as pertinent now as it was when it lambasted the privileges of the French aristocracy, shortly before the French Revolution of 1789.

Pierre Beaumarchais, the author of the play, was an 18th Century polymath, i.e. someone who mastered several different trades and professions. In his time, he was a watchmaker, an inventor, a musician, a diplomat, a spy, an arms dealer and until it got to sticky a participant in the French Revolution.

The Marriage of Figaro, the play, is the second part of a trilogy beginning with The Barber of Seville, where Figaro, a barber, helps a disguised Count Almaviva woo and marry Rosina. The Marriage of Figaro takes place three years later when the Count is sexually coveting the Countess’ ladies maid, Susanna, who just happens to be Figaro’s fiancée. Since Figaro has been upgraded to valet, the situation is a more than a bit messy.

However, the Count has generously, in the fashion of the Enlightenment, publicly abolished the droit du seigneur. Or ius primae noctis, i.e. the right of the first night. This meant that when a female serf married, the lord had the right to sleep with her on her wedding night. Historians agree that there was never any legal evidence for this, but like all myths, it was true in essence if not in fact, and succinctly explained realistic social dynamics. Feudal lords often had the free run of the household staff and the peasants and quite often if a pregnancy arose, would “persuade,” with a hunk of cash, one of the male staff to step in as a husband and father.

The play and the opera illustrate a great maxim about power relationships. A man with social dominance, in this case a feudal lord, is allowed to do whatever he wants with someone lower down on the social dominance scale, but if a woman in a socially dominant position is in a sexual relationship with someone lower down on the scale, all hell breaks loose. The aristocratic Count is free to fiddle with the servants, but the valet cannot fiddle with the Countess.

This message was highly controversial on the eve of the French Revolution. In fact, Beaumarchais went through several rounds with the official censors both before and after the play opened to great critical and popular acclaim at the Comédie Française in 1781. It was also popular with the French Revolutionaries such as Georges Danton, who said it “killed off the nobility.” Mozart experienced the same political difficulties, when the Opera opened in Vienna.

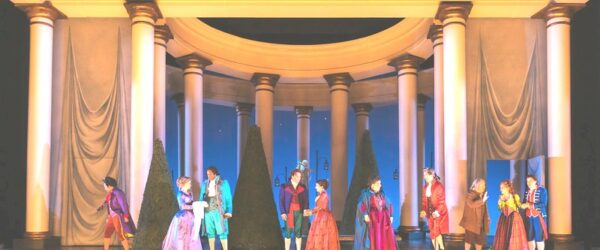

Although the singing, acting, and direction of Seattle Opera’s production was worthy of the greatness of Mozart and Beaumarchais, and was as good as any production I have seen, the set and costumes, upstaged the actual story. In any show, whether opera or theater, everything has to serve “telling the story,” even the singing. A singer who does not communicate to the audience the emotions of the song, but just shows off her high notes, fails. This did not happen in this show, but the set, beautiful as it was, completely overshadowed the singers. It was so massive that it made the singers look like miniature replicas of their characters.

Then there were the costumes. Although well made and historically accurate, the colors used were garish and the combination of colors did not blend well on stage. For example, one couple found the male, Dr. Bartolo, clad in tomato red, while he was standing next to his female partner in crimson red. The combination was unfortunate.

Using a proscenium stage the director should think of creating a picture. The costumes were imported from another production, but except for a few exceptions, the costumes of the principles, were a distraction from the story and visually unattractive.

Otherwise, the show was well directed, the comical acting of the cast was exceptional; there was lots of stage business added to the script to make this a good piece of theater. Stand outs were: Soroya Mafi as Susannah, whose arias were to die for, Ryan McKinny as Figaro, whose deep baritone and comic timing were outstanding. I particularly loved Norman Garrett as Count Almaviva, who emanated power, a sense of entitlement, and aristocratic privilege not just by his voice, a deep bass, but also by the way he walked! Marjukka Tepponen as the Countess was exquisite, as was Olga Syniakova as Cherubino. Although she played a smallish part, Ashley Favian as Barbarina, exuded youthful perkiness.

It was an impressive show, and there were standing ovations.

The Marriage of Figaro, Seattle Opera, McCaw Hall, Seattle Center, 321 Mercer St Seattle, 98109 May 7, 8, 11, 14, 18, 20, 21 & 22, 7:30 pm. May 15, 2 pm Info: Tickets: Parking at 650-3rd Ave N, Seattle, 98109, Bus #8 or mono-rail.