A Victorian Tale of Sadness and Compassion

Along with Jack the Ripper, the story of the Elephant Man is one the most intriguing stories of the Victorian era. Neither ever satisfied human curiosity by tying up the loose ends. The identify of Jack the Ripper is still unknown and to this day the cause of the Elephant Man’s deformities is still a mystery to scientists.

John (or Joseph) Merrick was born in 1862 in Leicestershire in the U.K. At the age of five he began to develop severe abnormalities; his skin became leathery and grey and his skull began to grow outwards so that his head was abnormally large. After leaving school at the age of 14, which was normal in those days, he did factory work for a while, but eventually found his way to that Victorian version of a concentration camp-the workhouse. Deciding that his only escape, was to exhibit himself in a freak show, Mewrrick willingly chose to do so. While being exhibited in the Whitechapel neighborhood in the East End of London, across the street from the London Hospital, a Dr. Frederick Teves, took an interest in him medically and later befriended him.

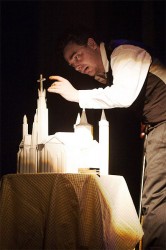

As a result of Dr. Teves intervention, his case became famous, and he was allowed to stay in the hospital under humane conditions. He spent his remaining years building model churches out of paper card, reading and weaving baskets while surprising many people with the intelligence of his conversation and the wisdom of his insights. He died at age 27, while sleeping lying downrather than sitting up, because the weight of his head crushed his esophagus.

The play The Elephant Man by Bernard Pomerance, written in 1977, opened at the Hampstead Theatre in London, moved to the National Theater and had a long run on Broadway. In 1980, David Lynch made a successful black and white film starring Anthony Hopkins. Both the play and the movie revived scientific interest in the case.

Although the Stageright’s Production at Inscape was stunning and in many ways overcame most of the flaws of the play, generally the material is just not suited for the stage. It is mostly anecdotal, there is little to drive the plot, no dramatic arc, in spite of the intriguing subject matter. One can argue that the subject matter itself leaves the audience with too many unanswered questions: what caused Merrick’s deformity and what could possibly cure it. The two leading theories today are either Neurofibromatosis type I or Proteus disease, a genetic disorder, however no definitive cause has ever been discovered and very few other cases have ever been recorded in medical history.

However, the acting was solid, with stellar performances by Brian Lange as Frederick Teves the surgeon who rescues and befriends Merrick, and Matthew Gilbert as John Merrick himself. In the original play, as in this one, Merrick’s condition was suggested by facial expressions rather than elaborate make-up, and Gilbert’s ability to physically inhabit the character of a severely deformed man was superb. Lorrie Fargo as Mrs. Kendal, a down-to-earth Victorian actress, who learns a few things from Merrick while visiting him, provided a great deal of comic relief.

The direction by Robert Bogue was generally solid, although being of average height and sitting in the back row, the scenes taking place on the floor were difficult to see, and some of the lines of Merrick were incomprehensible. The high-point of the evening was the set and the brilliant special effects by Brendan Mack

The play has a lot of short scenes and many scene changes which make it very difficult to stage, this production used supertitles, written in an old-fashioned script over the stage, to help move things along. The supertitles commented on the action, expressed the subtext, helped create the old-fashioned Victorian ambiance and seemed almost like a silent movie-N.B. the first recorded silent movie was made two years before Merrick died.

The recorded sound design by John R. Huddlestun was especially effective with mournful Victorian music. In addition, cellist Roland Carette-Meyers played his original compositions along with works by Tristan Carruthers and J. Bravel. The combination of the live music and the recorded music added significantly to the alternating feelings of sadness and hope expressed by Merrick’s plight.

It also seemed no accident that Right-stage chose The Lab@Insape, the theatre in the old Immigration Jail., to stage this play. The building itself reminds me of some of the Victorian-era hospitals in the U.K., so the atmosphere of the late 19th century begins at the box-office. All in all, it is worth seeing and not the sort of play one sees very often in Seattle.

The Elephant Man by Bernard Pomerance. STAGEright. TheLab@Inscape. 815 Seattle Blvd S. ( International District) Seattle, WA , Thurs, Fri, Sat. Through March 22nd. www. seattlestageright.org Tickets: www. thelephantman.brownpapertickets.com/